1. Part 1: Registration of Overseas Entities

Part 1 of the ECA sets up a register of overseas entities which will include information about their beneficial owners, and makes provisions "compel[ling]" overseas entities to register if they own land.

The register is to be maintained by the registrar of companies, and various criminal offences are created - most punishable by both fines and imprisonment - for those who fail to register their beneficial owners or who provide false information.

Who has to register?

Broadly speaking, the ECA applies to "overseas entities" (i.e. legal entities governed by a law of a territory outside of the UK): s. 2(1). For these purposes, legal entities include bodies corporate, partnerships or other legal entities recognised as such by the law by which they are governed: s. 2(2).

The obligation to register kicks in where the overseas entity owns land in the UK: see ss. 33-34 of the ECA.

Registrable beneficial owner

The first important concept introduced by the ECA is that of the "registrable beneficial owner": see Schedule 2. This applies where a person:

- Holds, directly or indirectly, more than 25% of the shares in an overseas entity.

- Holds, directly or indirectly, more than 25% of the voting rights in an overseas entity.

- Holds the right, directly or indirectly, to appoint or remove a majority of an overseas entity's directors.

- Has the right to exercise, "or actually exercises", significant influence or control over an overseas entity.

Information to be provided

Where an overseas entity is obliged to register, it must provide the "required information" (identified in Schedule 1). The information which must be provided falls into three categories.

Information about overseas legal entity (Schedule 1, Part 2). This information comprises the name of the overseas entity; its country of incorporation, governing law and legal form; its registered or principal office; a service address; an email address; and its registration number (and other details about any public register on which it is to be found).

Information about registrable beneficial owners (Schedule 1, Part 3). This is at the heart of the ECA regime - and the information that has typically been hidden hitherto. Beneficial owners must give their name, date of birth and nationality; their usual residential address and a service address; the date on which they became a registrable beneficial owner; and certain other information, including whether they are a sanctioned individual.

Information about managing officers (Schedule 1, Part 4). Where a legal entity either claims to have no registrable beneficial owners, or says that it has reasonable grounds to believe that there is such a beneficial owner but that he cannot be identified, an extra obligation kicks in: the legal entity has to provide information about "each managing officer". The purpose is pretty obvious: so that the authorities can ask for further information as appropriate.

Information about managing officers comprises their name, date of birth and nationality; any former name; their usual residential address and a service address; their business occupation; and a description of the roles and responsibilities they fulfil in relation to the legal entity.

Updating and removal

Overseas entities must update the information they are required to provide under the ECA each year: s. 7(9). Notably, the entity and every officer in default can receive a fine of £2,500 for each day they are in default of providing updated information: s. 8(2).

Overseas entities can also apply to be removed from the register, on the basis that they no longer own any UK land: s. 9(1)(a). But the registrar cannot process any such application unless he has checked with the Land Registrar that this is true: s. 10.

Giving the ECA teeth: information notices

The disclosure obligations could be easily evaded if an overseas entity could simply say "I don't know whether I have any registrable beneficial owners".

It is for this reason that s. 12 requires an overseas entity to take reasonable steps to identify its registrable beneficial owners. Importantly, these steps include

"giving an information notice ... to any person that it knows, or has reasonable cause to believe, is a registrable beneficial owner in relation to the entity." (s. 12(3))

An 'information notice' is a notice requiring its recipient to (a) confirm whether he is a registrable beneficial owner and (b) (if so) provide, confirm or correct the Schedule 1, Part 3 information that must be provided about him.

Indeed, s. 13 of the ECA gives an overseas entity the power to serve an information notice on any person who it knows or has reasonable cause to believe may know the identity of a registrable beneficial owner.

The ss. 12-13 obligations are backed by criminal sanctions: a person who fails, without reasonable cause, to comply or who makes a statement which is knowingly or recklessly false is liable to a jail term not exceeding two years, or a fine, or both: s. 15.

Inspection of the register

Subject to not being able to access dates of birth or residential addresses and a limited number of other exceptions, ANYONE can access the register: ss. 21-22.

2. How will Part 1 change property transactions?

The ECA contains a number of different provisions affecting property transactions by overseas entities.

The ECA is not a model of drafting perfection, no doubt because of the speed with which it was passed. But the two key points seem to be as follows.

(1) Amendments to the Land Registration Act 2002

Section 33 of the ECA implements changes to the Land Registration Act 2002 ("LRA"). The detail is found in Schedule 3, which introduces s. 85A and Schedule 4A into the LRA. In summary, these changes:

- Apply to freehold estates and leasehold estates granted for a term of more than 7 years. See LRA Sch 4A, para 1.

- Prohibits the making of any application to register an overseas entity as the proprietor of a property UNLESS the overseas entity is already a registered overseas entity (or is otherwise exempt). See LRA Sch 4A, para 2.

- Requires the Chief Land Registrar to enter a restriction on the title entry if (a) an overseas entity is registered as the proprietor of an estate AND (b) that estate was registered on or after 1 January 1999. The effect of the restriction will, in broad terms, be to prevent the property being sold unless and until the overseas entity appears on the register. See LRA Sch 4A, para 3.

(2) Transitional Provisions

Next, an offence is committed for those overseas entities (and each of its officers) if the overseas entity in question fails to apply to be registered before the end of the transitional period: see LRA Sch 4A, para 5.

Finally, an offence is committed by s. 42 of the ECA if an overseas entity makes a disposition of land at any stage between 28 February 2022 and the end of the transitional period (probably 15 September 2022: see s. 41(10)) UNLESS the overseas entity has during that period provided the registrar of companies with information about its registrable beneficial owners: see s. 42(1).

3. Part 2: Revamping UWOs

Part 2 of the ECA seeks to re-vamp Unexplained Wealth Orders ("UWOs").

UWOs were introduced, to great fanfare, by the Criminal Finances Act 2017. That legislation came into force in January 2018 and was expected to provide the NCA with a critical tool in combatting money laundering and the influx of dubious offshore wealth into the London property market.

Those aims were not met, with UWOs only being granted in four cases between January 2018 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

One of the key problems was the costs exposure faced by the NCA if it lost applications: in NCA v Baker, decided in early 2020, the NCA faced a costs exposure of c. £1.5 million; and no further UWOs have been sought since.

Part 2 of the ECA seeks to revamp UWOs. It is addressed at length on our Unexplained Wealth Order page. But, in summary, its five key reforms are as follows:

- To limit enforcement authorities' costs exposure to cases where they have acted unreasonably, improperly or dishonestly. See the new s. 362U of POCA.

- To expand the circumstances in which UWOs can be granted. Previously, a respondent's lawful income had to be insufficient to explain his ownership of property. But this rendered UWOs ineffective when a person suspected of criminal activity had some legitimate wealth. Now an alternative test is introduced: reasonable suspicion that a particular property has been acquired through unlawful conduct. See the new s. 362B(3)(b) of POCA.

- To enable UWOs to be granted against responsible officers of corporate respondents (i.e. directors or those fulfilling similar functions), increasing the prospects of high quality information being provided in answer to their disclosure provisions. See the new s. 362A(2A) of POCA.

- To provide enforcement authorities with up to 186 days to decide how to respond to the information provided pursuant to a UWO - trebling the original 60-day limit. See the new s. 362DA of POCA.

- Requiring the Secretary of State to provide annual reports to Parliament explaining how often the UWO legislation had been used in the previous year - a stick to ensure that enforcement authorities use the new UWO toolkit that has been made available to them. See the new s. 362IA of POCA.

4. Part 3: Streamlining Sanctions

Part 3 of the ECA seeks to streamline some of the bewildering complexity surrounding sanctions.

For those who don't know their way around the sanctions legislation, here's a starter guide:

-

The key sanctions Act is the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 ("SAML18"). It introduces five key types of sanctions (i) financial sanctions (to freeze the assets of politicians and oligarchs that the FCO decides to target), (ii) trade sanctions (to prevent English companies from trading in specified industry sectors or goods with, say, Russian companies), (iii) immigration sanctions (to stop designated persons coming to the jurisdiction), (iv) aircraft sanctions (to stop planes belonging to designated persons coming into the jurisdiction, and to impound them if they do), (v) shipping sanctions (to do the same types of things in relation to ships). It also introduces the concept of a 'designated person' - someone who is sanctioned. And there is machinery for Ministerial and Court reviews of sanctions that have been imposed. But, crucially, all of the detail surrounding the nature of sanctions to be imposed is left to secondary legislation that the SAML18 gives Ministers the power to enact ("Sanctions Regulations").

-

There are loads of Sanctions Regulations, and they are really long. The most important for present purposes is The Russia (Sanctions) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 ("Russian Regulations"), which have been regularly amended (eight times between January and April 2022, for example). It is here, for example, that you find out what financial sanctions imposed against designated people actually prevent. It is here that you find the eye-watering detail in relation to what can (and cannot) be sold to Russia. And it is here that you learn of the penalties applies to those who breach sanctions. But, with a handful of exceptions, designated persons are not included within the 180-odd pages of the Russian Regulations.

-

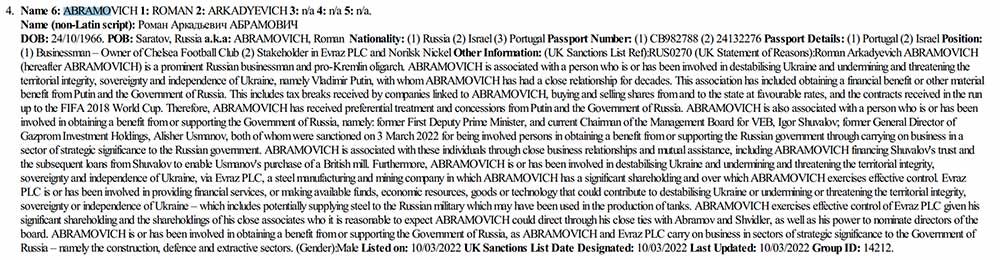

To work out who is actually designated, you will need to consult the Office for Financial Sanctions Implementation's ("OFSI's") most recent 'consolidated list'. OFSI, part of the Treasury, publishes new designations and then adds them to its consolidated list on a regular basis. The entry for Roman Abramovich on that list reads as follows:

Against that background, Part 3 of the ECA makes the following changes to the sanctions legislation.

First, it seeks to streamline way in which sanctions can be implemented, and indeed standardise sanctions efforts between Western allies. More specifically, it provides that Ministers can impose sanctions on individuals under an 'urgent procedure' in the event that (a) one of a number of trusted countries has imposed sanctions and (b) the Minister considers that it is in the public interest to use the urgent procedure. The trusted countries include the USA, the EU, Australia and Canada.

Secondly, it makes it easier for the Treasury to impose a monetary penalty for breaching sanctions regulations. Previously, this power had been conferred on the Treasury (in reality OFSI) by s. 146 of the Policing and Crime Act 2017, but it was subject to the Treasury being satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the person to be penalised knew, or had reasonable grounds to suspect, that he was acting inconsistently with sanctions legislation. That restriction is jettisoned, and so penalties can be imposed on a strict liability basis. Indeed, a new s. 146(1A) is introduced which says that

"... any requirement imposed by or under that [sanctions] legislation for the person [to be penalised] to have known, suspected or believed any matter is to be ignored."

Thirdly, a host of reporting obligations imposed on Ministers and departments by SAML18 are jettisoned by ss. 62-63 of the ECA. Indeed, the Court's power to award compensation for the improper imposition of sanctions is substantially attenuated: now the Minister must have acted in bad faith, and the damages the Court can award are capped at an amount to be specified in new regulations: s. 64 of the ECA.